Born on December 7, 1909, in Waterbury, Connecticut, Kainen was the second of three sons of Russian immigrants. His father Joseph was a tool-and-die maker and an inventor, whose inventions included the “Dead Man’s Brake,” which shuts down a train in case of emergency (family lore says the patent was stolen from him). He was a mechanical whiz who owned his own watch company at one point and occasionally sculpted. Kainen’s mother Fannie (née Levine) had no formal education, but had a great appreciation for music, art and literature and was known for her good taste. Both parents encouraged their boys ⎯ Jacob, Abe, and Eddie ⎯ in their artistic and academic pursuits.

When the family moved to the Bronx in 1918, Kainen’s budding passion for art and literature was fueled by trips to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where his mother would pick out paintings for him to copy as gifts, and the New York Public Library. In addition to exercising his natural artistic skills, he became a prodigious reader and showed a gift for memorizing poetry by the time he was in the sixth grade.

After graduating from DeWitt Clinton High School at sixteen, Kainen took drawing classes at the Art Students League, where Kimon Nicolaides taught him to respect artistic discipline and to trust in the freedom and sureness of his hand. Kainen later said that the Nicolaides classes were the best training he ever had. It was during this time that Kainen made his first prints by pulling drypoints on zinc plates through the ringer of his mother’s washing machine.

At the same time, Kainen indulged his love for literature by working in the classics department of Brentano’s bookstore and developed his skills as a boxer, prompted years earlier as he fought off neighborhood bullies. These experiences served him well as he went on to become an expert in the classics and a skilled amateur prizefighter.

Kainen was admitted to the Pratt Art Institute in 1927. After several years of art training and constant work on his own, Kainen was far more advanced and ambitious than most of his fellow students and knew more than some of his teachers. While he had a deep appreciation for the old masters, he quickly found the curriculum backward, anti-modernist, and rigid. In Kainen’s final year at Pratt, the fine arts curriculum was revamped as a commercial art program, and Kainen was outraged. He rebelled by refusing to take commercial courses and set up his own class. He was expelled three weeks before graduation. (He would finally receive his diploma from Pratt twelve years later.)

This event proved monumental in Kainen’s conceptual and artistic development. He sought out other avant-garde artists in the city, especially those who shared his institutional contempt. He began to engage with the emotive palette and gestures of German expressionism and the social awareness and ferocity of Social Realism during the 1930s. Kainen also frequented cafeterias that had become the places where urban artists met to debate and develop ideas, both social and aesthetic. In the early 1930s, Kainen formed close friendships with the early abstractionists, including John Graham, Stuart Davis and Arshile Gorky, who painted his portrait and became his mentor. Kainen’s influences from the New York School and his admiration for the great expressionist artists remained a constant throughout his life.

An artist is working in a rectangle and everything he has seen and heard is part of his point of view…. Gorky gave me advice: “Above all, trust your unconscious.” When I was 24. I didn’t quite understand what he meant. I had a very uninteresting unconscious at 24.

It was during this time that Kainen joined the Artists’ Union and became a contributor to, and later editor of, its journal, Art Front, and an occasional cartoonist and reviewer for The Daily Worker. He also signed legal petitions to institute social change. These activities would come back to haunt him years later.

From 1935 to 1942, Kainen worked for the Graphic Arts Division of the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA) Federal Arts Project, a New Deal program that employed artists. He was able to learn lithography, etching, woodcut, silkscreen, and other media as part of this project while saving his personal time for painting. He soon began to enjoy printmaking as his skills and confidence increased and he found he could bring his painting skills to bear on the medium by working freely, expressively, and seeking new means of introducing textures and tones. As with his paintings, his subject matter was the city’s people and places, based on his observations of the realities of the Depression. He learned color printing, and two of his finest prints, Banana Man (1938) and Snowfall (1939) are complex experiments that would have been beyond him at the beginning of the project.

Painting is one thing, but to be able to make prints is another. Because you have this graphic sense, a sense of black, white and gray and the calligraphic or tonal sense. That’s why it’s so attractive to painters, to artists…. a woodcut or a lithograph, an etching or a silkscreen has a physical property that is distinct from all others.

During the late 1930s, Kainen and seven other painters Alice Neel, Jules Halfant, Herbert Kruckman, Louis Nisonoff, Herman Rose, Max Schnitzler and Joseph Vogel formed the New York Group, an exhibiting body that Kainen wrote “is interested in those aspects of contemporary life which reflect the deepest feelings of the people; their poverty, their surroundings, their desire for peace, their fight for life.” His expressionist and social leanings began to definitively merge in his work. The New York Group exhibited twice at New York’s A.C.A. Gallery and Kainen had his first solo show there in 1940.

During the late 1930s, Kainen and seven other painters Alice Neel, Jules Halfant, Herbert Kruckman, Louis Nisonoff, Herman Rose, Max Schnitzler and Joseph Vogel formed the New York Group, an exhibiting body that Kainen wrote “is interested in those aspects of contemporary life which reflect the deepest feelings of the people; their poverty, their surroundings, their desire for peace, their fight for life.” His expressionist and social leanings began to definitively merge in his work. The New York Group exhibited twice at New York’s A.C.A. Gallery and Kainen had his first solo show there in 1940.

In 1942, as prospects at WPA looked dim, Kainen made the life-changing decision to leave New York and move to Washington, D.C. to work as an aide for the Division of Graphic Arts at the Smithsonian’s U.S. National Museum (now the National Museum of American History, Kenneth E. Behring Center). He hated leaving New York, his friends and fellow artists, but he needed steady work and thought the move to Washington would be temporary.

Kainen was immediately shocked by the state of Washington’s rudimentary, slow-paced art scene, a wasteland for contemporary art. He would become a major force in turning that around.

What I found particularly conspicuous, like missing a front tooth, was the lack of an older generation of ambitious artists, that we, the upcoming generation, could look up to and cross swords with…. It was difficult to start out in Washington like Robinson Crusoes.

In the years that followed, becoming assistant curator in 1944 and curator in 1946, he completely reshaped the Division of Graphic Arts, built the graphic arts collection, and helped create the postwar Washington art scene. His print exhibitions brought the work of S.W. Hayter, Josef Albers, Adja Yunkers, Louis Lozowick, Karl Schrag, José Guerrero, Louis Schanker, Werner Drewes and Boris Margo to Washington audiences.

In the years that followed, becoming assistant curator in 1944 and curator in 1946, he completely reshaped the Division of Graphic Arts, built the graphic arts collection, and helped create the postwar Washington art scene. His print exhibitions brought the work of S.W. Hayter, Josef Albers, Adja Yunkers, Louis Lozowick, Karl Schrag, José Guerrero, Louis Schanker, Werner Drewes and Boris Margo to Washington audiences.

Kainen’s own paintings from the 1940s illustrated a shift away from Social Realism toward abstract expressionism. He found inspiration in the Victorian skyline and architecture of the buildings surrounding his studio in Dupont Circle. He was one of the first abstract artists working in the city and produced abstract compositions of symbols and forms that resounded with both his physical surroundings and personal experiences.

In 1946, Kainen was included on Ad Reinhardt’s “Tree of Modern American Art,” a succinct map of the artists and movements defining art of the modern era. In 1947, the Washington Workshop Center for the Arts opened its art school, and Kainen served as a painting and printmaking teacher and guide to many important artists. He helped to make the workshop a magnet for new talent and instrumental in furthering the careers of artists such as Gene Davis, Morris Louis, and Alma Thomas.

It’s only in an affluent time that artists want to put “life” into their work. When times are hard, you don’t need to; you take it for granted. Getting up, your daily activities… you take them for granted.

I had done things as a noble gesture. I thought I was on the side of the angels, contributing to a fair and sane society. Instead, I found myself regarded as an enemy of the people, a traitor. It would make any idealist silent-mute.

In 1946, Kainen was included on Ad Reinhardt’s “Tree of Modern American Art,” a succinct map of the artists and movements defining art of the modern era. In 1947, the Washington Workshop Center for the Arts opened its art school, and Kainen served as a painting and printmaking teacher and guide to many important artists. He helped to make the workshop a magnet for new talent and instrumental in furthering the careers of artists such as Gene Davis, Morris Louis, and Alma Thomas.

In 1949, the Corcoran Gallery of Art held a retrospective of Kainen’s prints. That same year, his national loyalty was questioned and he was placed under investigation by the Civil Service Commission’s loyalty board because of the petitions he signed and articles he wrote for leftist causes as a young man in New York. As explained in the book Washington Art Matters,* “He watched as Congress pressured government agencies to fire anyone who was ‘not in the best interests of the department’… Kainen kept his job for two reasons–one, the attitude of superiors at the Smithsonian, people, he said, ‘accustomed to dealing with ideas,’ and two, an earlier commendation by J. Edgar Hoover himself….Kainen had earned the FBI’s gratitude by teaching printing methods to agency trainees, and Hoover had sent a letter saying, ‘You’ve done our country a great service.’ When the FBI rediscovered this bit of history, the visits stopped.”

In 1949, the Corcoran Gallery of Art held a retrospective of Kainen’s prints. That same year, his national loyalty was questioned and he was placed under investigation by the Civil Service Commission’s loyalty board because of the petitions he signed and articles he wrote for leftist causes as a young man in New York. As explained in the book Washington Art Matters,* “He watched as Congress pressured government agencies to fire anyone who was ‘not in the best interests of the department’… Kainen kept his job for two reasons–one, the attitude of superiors at the Smithsonian, people, he said, ‘accustomed to dealing with ideas,’ and two, an earlier commendation by J. Edgar Hoover himself….Kainen had earned the FBI’s gratitude by teaching printing methods to agency trainees, and Hoover had sent a letter saying, ‘You’ve done our country a great service.’ When the FBI rediscovered this bit of history, the visits stopped.”

*Washington Art Matters: Art Life in the Capital 1940-1990 by Jean Lawlor Cohen, Sidney Lawrence, and Elizabeth Tebow, with afterword by Benjamin Forgey (2013)

Kainen was not cleared of formal charges until 1954. The strain of this period became evident in his vivid abstractions with titles like Exorcist (1952) and Unmoored #2 (1952). Kainen later remembered this as a period when “I begin with the aesthetic balancing of forms, but these psychological ghosts take over.”

Kenneth Noland organized Kainen’s first retrospective at Catholic University in 1952. Kainen later called the show, which included fifty to fifty-five paintings, one of the most important of his career. In the mid-1950s, Noland and Morris Louis established the basis for the Washington Color School. Because Kainen defined the fundamental concept of Washington Color Painting as staining, he never considered himself a member of the Washington Color School or a Color Field painter. Also, by that period, Kainen rejected the popularity of abstract expressionism for a return to the figure and shifted his focus to elegant figurative work.

In addition to pursuing his own art and curatorial duties for the Smithsonian Institution, as well as teaching and mentoring, Kainen engaged his literary side with research and writing. He published numerous books, articles, exhibition catalogue and book forewords. In 1956, he received a grant from the American Philosophical Society to conduct research in Europe on English woodcut artist John Baptist Jackson. This resulted in his acclaimed monograph John Baptist Jackson: 18th-Century Master of the Color Woodcut. He traveled to Europe again in 1962 to study paintings and prints from the Mannerist Period. His book The Etchings of Canaletto was published in 1967. He also wrote poetry throughout his life, but declined to have it published despite urging from family and friends.

By 1966, Kainen was tired of his dual careers as an artist and curator and attempted to retire from the Smithsonian. David Scott, director of the National Collection of Fine Arts (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum), persuaded him to become a part-time curator of prints and drawings at his museum. Kainen’s so-called part-time position stretched into long hours and between 1966 and 1970, he increased the collection from 1,000 to 7,000 works.

That’s the trouble with art that depends just on surface attractiveness, a certain charm. When you think of the other arts — poetry, the novel, music — in all the best painting there’s a bigness of feeling; you get more than just a nice picture, right?

Kainen and his wife Bertha divorced in 1968. In February 1969, Kainen married writer and art collector Ruth Cole. Their home in Chevy Chase, Maryland became a gathering place for the Washington art world, and Kainen often entertained guests by reciting from memory passages from his favorite writers, including Keats, Yeats, Milton, and Melville.

In their 32 years together, the Kainens built one of the finest collections of 20th-century German expressionist prints and drawings in private hands, as well as outstanding works by 16th-century Dutch mannerists and 20th-century American abstract expressionist artists. They also became major benefactors of the National Gallery of Art, Baltimore Museum of Art, the Jewish Museum New York, and other museums.

Kainen retired from the Smithsonian Institution in 1970 to devote himself full-time to his art, but continued to serve as a special consultant to the Smithsonian American Art Museum for nineteen years. In 1971-1972, Kainen taught painting and the history of printmaking at the University of Maryland.

Like most artists, I am particularly fond of Keats’s letters, which strike a vividly contemporary note. He was heavy on trusting one’s imagination, on scorning logic and reason in conceiving poetry…. It should always be open to the imaginative digression—don’t worry about the “anonymous” reader or critic. And what is more up-to-date than the remark, “What shocks the virtuous philosopher delights the chameleon poet?”

Between 1970 and 1980, Kainen had at least one show of oils or works on paper a year, including an exhibition at the Pratt Manhattan Center in 1972, two shows at the Phillips Collection in 1973 and 1980 and two shows at the National Collection of Fine Arts (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum) in 1976 and 1979. Many of the artists he befriended and supported through the years attended these exhibits.

After his retirement from the Smithsonian, Kainen’s work shifted back to pure abstraction, yet this body of work contrasted dramatically with his abstraction from the early 1950s. These paintings no longer reflected the stress of persecution, but rather conveyed the tranquility he found later in life.

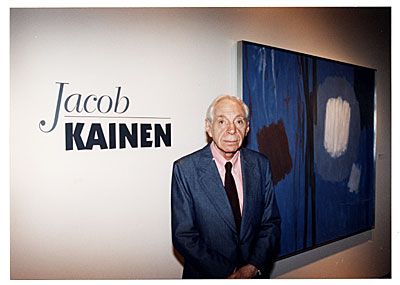

A major 100-piece, 60-year retrospective of Kainen’s paintings was held in 1993 at the National Museum of American Art (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum). Other exhibits, including three at Hemphill Fine Arts in Washington, followed in 1997-2001.

In a 1997 interview, Kainen estimated he’d done 1,000 paintings in his lifetime. He continued to work in his studio up to the end. He died on March 19, 2001, at the age of 91. He was survived by his wife Ruth (who died in 2009) and his sons Daniel, an artist/designer/inventor/author, and Paul, a mathematician and author.

For additional information about Jacob Kainen’s life,

please click on these links:

Professional Chronology

Oral History Interview with Avis Berman

Hemphill Fine Arts

It is difficult to say what I am thinking of when I begin a painting. I have a certain ethical concept in mind, mostly against. I believe what I have in mind is more a feeling of great spirits, real presence, of an ancient mentor. It’s just something in the back of my mind, nothing really concrete. The idea is to give spiritual nourishment. So you put into it spiritual feeling.